Can benefits outweigh pay in a job seeker's decision?

Cash may be king, and certainly employees and job-seekers today always look at pay first. But when it comes to return on spend, employers are likely to find that one dollar spent on employee benefits has a disproportionately larger impact on engagement – and by extension performance – than that same dollar put into the salary budget.

Why is this the case, and what are the implications for benefits and engagement strategies? People Matters spoke with Royston Tan, WTW's international head of strategic growth for its health and benefits business, for some insights on what the data says and what actionables might work for organisations in the current economic environment.

Medical inflation and the shrinking of real wages

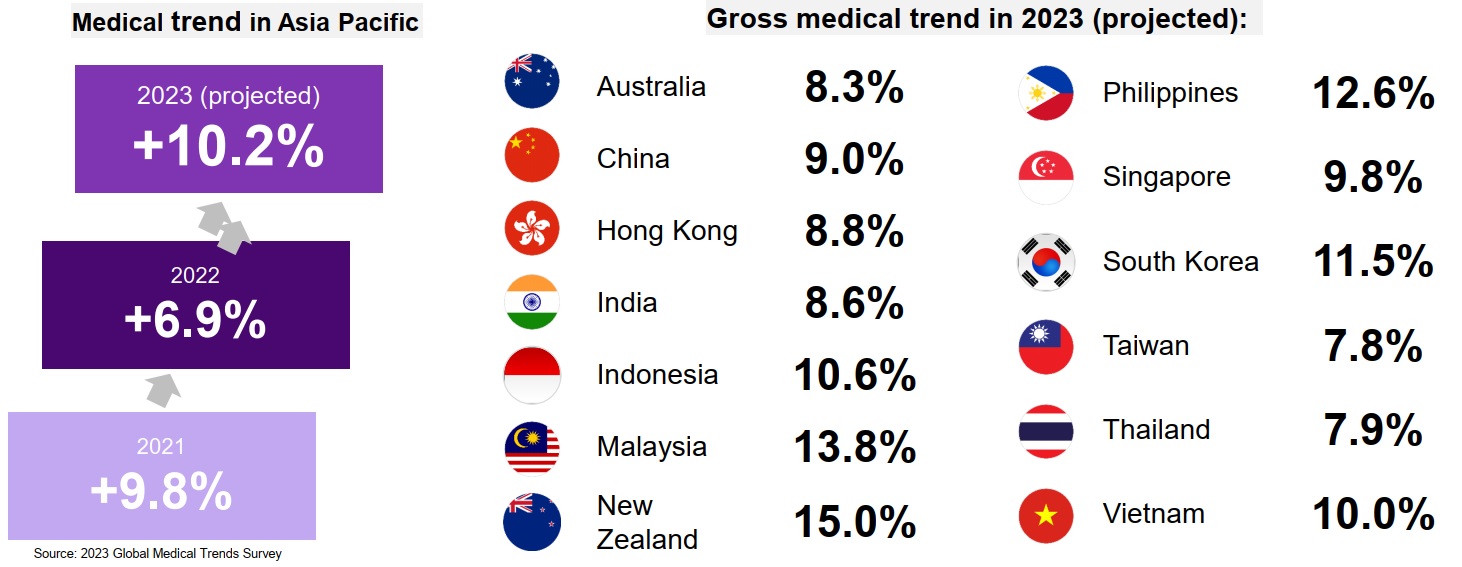

In today's inflationary environment, real wages have shrunk, and annual salary increases do not balance out increases in the consumer price index. At the same time, medical costs have been steadily increasing and are now at a 15-year high, with double-digit increases projected across most of Southeast Asia. The availability of medical services also remains stretched as a lag effect of the pandemic, with the backlog of delayed consultations and elective procedures still not fully resolved.

That adds up to mounting healthcare costs, with the burden spread unevenly between social security systems, employers, and employees.

“Healthcare expenses typically make up an overwhelming portion of what employers spend on benefits,” said Tan. “At the same time, employers continue to face constraints on the salary front. They therefore turn to benefits as a tool to differentiate and enhance their total rewards package. And we are seeing the more forward-thinking employers being more strategic not just about how they spend on benefits, but also about how they capture the value of the spend.”

The value of benefits spend: making people more likely to stay?

WTW data on employee attitudes to their benefits indicates that across the Asia Pacific, more than half of all employees are either actively looking for a job or ready to accept a good offer that comes their way. In countries seeing higher inflation and greater job pressures, that number mounts: in Singapore, for example, two-thirds of employees do not intend to stay with their current employer.

Unsurprisingly, the same data also shows that pay, bonuses, and job security are the top two attracting factors across all demographics. But following on those, flexible work and paid time off are the next most important to employees – these, in many cases, are the factors that will influence people to stay in a job or to accept a new offer.

“Let's say we have a colleague who has caregiving responsibilities,” Tan gave an example of how flexibility can sway someone's decision. “If a company does not mandate that he or she has to come into the office for a minimum number of days, and instead lets people come in based on job requirements, this flexibility is so great that even if a competitor offers more money but pairs it with the need to come in two or three days a week, that person might not want it because of his or her caregiving needs. This is where flexibility becomes a key differentiator.”

“It doesn't necessarily cost the company more, but it's something that the workforce wants as an option.”

So what should employers look at spending more on?

The importance that different demographics place on the secondary pull factors – flexible work, Paid Time Off (PTO), career advancement, sense of purpose, etc – varies based on an individual's life stage and their family and financial commitments. But it's not practical to customise benefits and messaging to individual circumstances. Instead, employers have been looking at core benefits, or minimum standards, on top of which some flexibility and personalisation can be provided.

The problem is, a large gap persists between what employers are looking at and what employees are hoping for.

“When we ask employers what they are planning to do with regards to their benefits strategy, their focus is on health care, training, development, life insurance, and so on,” said Tan. “But when we asked employees where they hope their employers can support them, or where they would like their employers to do more, you can see a massive divergence – they want support with their long and short term finances, their retirement plans, family and caregiving needs.”

“And this is quite understandable in the context of rising inflation. Just last year, our research found that employees were saving about 15% less than what they would have liked to, probably because of cost of living increases or family exigencies, and hence their retirement planning is slower than expected.”

Source: WTW's 2023 Benefits Trends Survey, Asia Pacific and 2022 Global Benefits Attitudes Survey, Asia Pacific

Can we fix this gap?

Part of the issue is a lack of data. Even though broader research has repeatedly substantiated that employers' and employees' focus does not match up, a large number of individual organisations do not have enough data on their own internal processes and situations to justify changing what they are doing. WTW's own research found that lack of data – to measure programme outcomes, to identify employee wellbeing issues, or even just on changes in employee behaviour – comprises two of the top three challenges to making wellbeing programmes effective, with cost being the number one challenge.

There is no quick fix to this solution, unfortunately – the one gap in the market highlighted here is the lack of a single integrated platform that can consolidate the large volumes of scattered data organisations generate.

But there are ways for HR teams to measure the value of a benefits and wellbeing investment, using metrics such as absenteeism, engagement scores, responses to pulse surveys, and overall changes in employee experience.

“It doesn't have to be something fuzzy and intangible – it is possible to show there's some level of value that can help build a business case for increased or continued investment in these programmes,” said Tan.

With that data, and using the model of core minimum (or foundational) benefits with flexibility above that, it should be possible for organisations to offer employees something that they will value more than a small pay bump from a competitor.

“Recruiting new talent creates high costs for the companies. Rather than giving up their jobs to fulfil family commitments or meet other needs, employers should consider offering people a compromise that they will be happy to take, especially in a competitive job market,” said Tan.

“Organisations need to be flexible enough to let people work in a way where they can still have their cake and eat it, even though it's not a beautiful cake.”