Utilising curiosity and competence to move up the learning curve

Over the course of the last 20 years, we have been in the business of assessing candidates – from freshers to C-Suite leaders – on the basis of their competence and potential. And what has been our most important learning in the last two decades? That competence and potential aside, it is curiosity that a candidate needs to move up the ladder.

Interesting, isn’t it? Now before we really dissect the above statement, let’s define the terms we’re discoursing.

Competence is the ability to be effective and efficient in a unique situation. This could include core, leadership, or functional competencies. It’s an observable and tangible quality that is vital to performance and job satisfaction. (Yadav, 2018)

Curiosity can be defined as a penchant for seeking new experiences, knowledge and feedback and an openness to change (Claudio Fernández-Aráoz, 2018). In the work environment, cultivating organization-wide curiosity helps leaders and their employees adapt to uncertain market conditions and external pressures.

The most enduring metaphor for curiosity is cognitive appetite (Loewenstein, 1994). Both appetite and curiosity are powerful drives that share similar underlying mechanisms. Appetite is the desire for food with the aim of reducing the physiological discomfort (i.e., the condition of inadequacy) of hunger, while curiosity is a desire for information in order to reduce the psychological discomfort of uncertainty

It was observed by Kashdan et al (2020) that there are four dimensions to workplace curiosity:

1) Joyous Exploration

2) Deprivation Sensitivity

3) Stress Tolerance

4) Openness to People’s Ideas

These dimensions predict significant outcomes such as work engagement, innovation, job crafting, and job satisfaction. They also found that workplace curiosity outperformed the trait of mindfulness in predicting the above outcomes.

There is some ambiguity between Curiosity and Interest. Situational interest is a positive effect (enjoyment and pleasure) generated by a particular stimulus that makes individuals approach it.

In contrast, Curiosity is seen as a standard homeostatic drive (i.e., maintaining a stable internal state) similar to appetite. The curiosity drive is reduced by filling the information gap, resulting in the reestablishment of cognitive equilibrium. This resolution of curiosity reinforces information-seeking behavior.

Differentiating between FOMO and genuine curiosity

The wide adoption of social media as an integral part of our day-to-day lives has had a number of disadvantages. And from an anthropological point of view, among the most pervasive has been that we are unable to differentiate between genuine curiosity and the usually shallow and superficial sense of FOMO (fear of missing out).

While curiosity is the desire to learn something new and expand your overall understanding of the world, FOMO is narrowly-focused, ego-centred. It wouldn’t be wrong to say that FOMO is almost an evil sibling of curiosity. When one’s behavior is influenced by FOMO, one may not really be interested in an event at all, but would still feign curiosity just “to be a part of” of something.

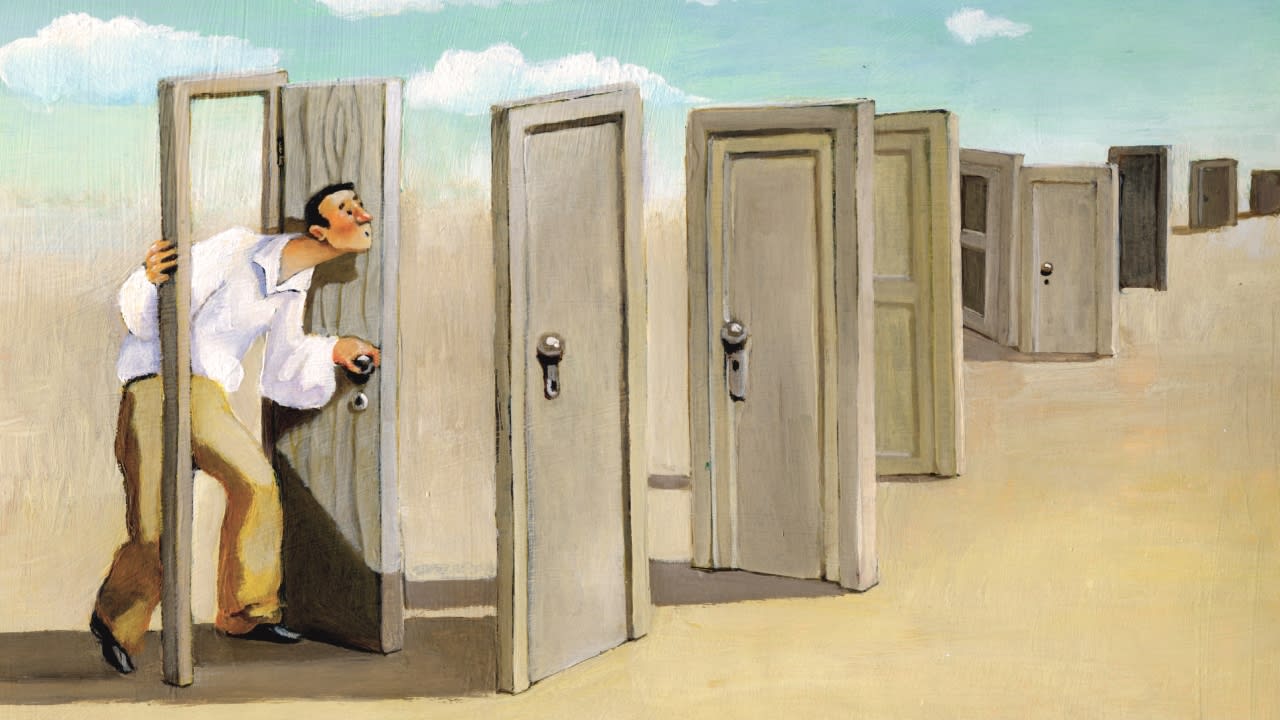

To understand the need for both competence and curiosity, let’s consider the following scenario: Shekhar displays great competency as a technology recruiter, and is promoted to the next role as a Team Leader. In this position, he displays great competencies as a people manager and is further promoted to the next role in the hierarchy. As time passes, he is promoted to a senior role for which he is not trained or prepared for — meaning that he would be more productive for the company if he had not been promoted – rendering him to be incompetent.

This paradoxical phenomenon is commonly known as The Peter Principle; employees rise up through a firm's hierarchy through promotion until they reach a level of “respective incompetence”. In our experience, most junior employees rely on facts and tangible skills to progress to the next stage in their career, whereas successful leaders rely on their curiosity to innovative new solutions and level-up the game. But, many-a-times, as you grow, you rely on your competence and learned subject matter expertise instead of going left of field to discover something new. When an employee’s curiosity is triggered, they think more deeply and rationally about decisions and tend to come up with more creative and innovative solutions. (Yadav, 2018)

It is this deep and rational thinking that makes curiosity a gateway to further competency.

Types of curiosity and its relation with uncertainty

Berlyne (1960) distinguished two types of curiosity — specific curiosity and diversive curiosity. Specific curiosity involves detailed investigation of novel stimuli, whereas diversive curiosity is the more unspecified exploration of the environment to find novel stimuli. Specific curiosity serves to decrease uncertainty whereas diversive curiosity is aimed at increasing uncertainty.

Curiosity: The gateway to competency

Curiosity acts as a powerful foundation, boosting the effects of nearly every other competency one might bring to the workplace. To better understand this, consider the relationship between curiosity and leadership competencies.

As a leadership fundamental, listening without comprehension is worthless. The mechanics of asking questions, nodding and saying “oh okay” lack heart without curiosity. Only a spirit of inquiry with genuine interest will unleash an outpouring of information from which the curious leader is able to benefit. The only way to improve business acumen and be truly competent – across horizontal and vertical promotions – is by being curious, asking questions and pushing yourself forward.

So, how does one become curious? Is it an inherent trait or a learned behaviour? Theories of curiosity often focus on curiosity as a stable personality trait. Are those with “child-like” curiosity destined to be competent leaders, or can an average Jai climb this ladder of curiosity as well?

A quick online search will show pages of results with links boasting of “7-step masterplan to ignite curiosity” and other such virtual courses. Clearly the market has identified a gap and is eager to plug it. One can sign up for a myriad of trainings, read books, or attend workshops to nurture their ability to question, connect the dots and find solutions. Dedicated and repeated efforts to be inquisitive - with intent - will help build one’s technical and soft skill aptitude.

Curiosity as a skill

However, the responsibility lies not just on the individual but also on the organization to which she/he/they belong. An ecosystem that encourages and trains its employees to actively hone curiosity as a skill (as opposed to just a nice-to-have personality trait), will soon see their company position morph from being fast-followers to first-movers. Every boardroom agenda includes some mention of innovation, but no indication on how to achieve said goal. If companies create structured initiatives that encourage and reward employees for their curiosity-driven results, it would level-up the competence and output of the overall organization.

Curiosity inhibitors

To begin the process of improving curiosity in the workplace, it is important to discover the factors that might impede curiosity. Diane Hamilton (2019) explored the inhibitors of curiosity in the workplace and came out with four factors

-

Fear

-

Assumptions

-

Technology

-

Environment

Hamilton used these dimensions to create Curiosity Code Index.

While Fear included failure, embarrassment, lack of control, Assumptions included lack of interest, laziness, lack of necessity. Similarly, while Technology included having technology solving issues for them, lack of exposure to technology, and too much information to process, Environment included the impact of educators, work relationships, and family, peers and friends.

Reward curiosity, not conformity!

As we can see, curiosity in employees is a valuable personality trait and should only be encouraged. In the words of Jeff Bezos “Let curiosity be your compass!”. As you navigate life – at home or at work – being curious will empower you to be more efficient, productive, sustainable and relevant; the more you question, the more you’ll know. In the end, your curiosity will make you more competent.

Bibliography

-

Yadav, M. (2018). Defining ‘Curiosity’ as a Key Competency. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR), 226.

-

Claudio Fernández-Aráoz, A. R. (2018). From Curious to Competent. Harvard Business Review.

-

Loewenstein, George. (1994). The Psychology of Curiosity. American Psychological Association.

-

Kashdan, Todd. (2020). Personality and Individual Differences - Curiosity has comprehensive benefits in the workplace. Science Direct.

-

Berlyne, D. E. (1960). Conflict, arousal, and curiosity. McGraw-Hill Book Company.

-

Markey, A., & Loewenstein, G. (2014). Curiosity. In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 228–245). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

-

Hull, C. L. (1932). The goal-gradient hypothesis and maze learning. Psychological Review, 39(1), 25–43.

-

Pintrich, P. R. (2003). A Motivational Science Perspective on the Role of Student Motivation in Learning and Teaching Contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 667–686.

-

Hamilton, Diane. (2019). Developing and testing inhibitors of curiosity in the workplace with the Curiosity Code Index (CCI). Heliyon.