Scenario Planning for Human Resources: Key to Agility and Anticipation

If we all knew exactly how the future would turn out, there would be no need to negotiate plans. We would simply accept the future and decide how best to provide for the needs of our organization — paths forward would be clear, and deviations will become choices, rather than necessities.

Unfortunately, despite what many futurists and forecasters say about the certainty of trends, their pronouncements, often delivered with great authority, come without context. Trends rely on social, political, economic, environmental and technological assumptions regularly unarticulated by those who dogmatize trends. Any change to the underlying assumptions, and the trend may well derail, leaving its followers reacting to change, rather than navigating it.

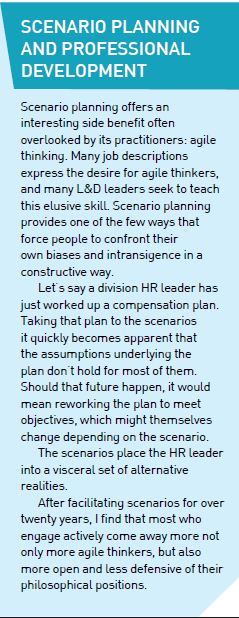

As much as we want to believe that trends will inform us and help us make better decisions, the only way to really improve decision-making is to embrace uncertainty and deal with the underlying complexity of the world. The discipline best suited for this work is called scenario planning.

Scenario Planning Fundamentals

Scenario planning comes out of war game analysis from the 1950s and 1960s. It has since been adopted by many of the most profitable and sustainable organizations around the world.

At its core, scenario planning creates multiple, purposefully divergent stories about the future. These stories emerge from research, understanding and synthesis of the uncertainties facing a company, an industry, a nation or an NGO.

The first task involves defining scope. In scenario planning, scope employs a focal question. For this article, assume the question: “What will HR mean to an organization in 2030?” In order to help the teams think even deeper about the influences on not just their roles, but why their roles exist, the question could also be broader, such as “What will work look like in 2030?”

For the scenarios to be meaningful, the organizations conducting the scenario work must look well beyond what they comfortably know. The next phase of most scenario projects involves what is known as “outside-in thinking”, which means that the teams look to the factors that influence the market, the resources, the regulations and other elements that create organizational context.

This research should include diverse voices. Homogeneous groups tend to feed confirmation bias, so scenario planning seeks a variety of inputs to initiate and feed its divergent stories.

Even if the incoming presumption for several factors points toward certainty, divergent viewpoints on topics quickly demonstrate the underlying uncertainties hidden behind unchallenged assumptions.

As a simple example of uncertainty, think about regulatory labor frameworks. In the United States, for instance, a rising “Gig Economy” exists. In the Gig Economy, many people take on jobs where they behave more like independent contractors than employees. This, combined with outsourcing, challenges traditional notions of employment which results in questions like: Who is responsible for talent management development in a Gig Economy? The failure to grapple with uncertainties often results in the unexpected undermining of plans because false assumptions get revealed too late. The rise of the Gig Economy disrupts labor-intensive markets like transportation and hospitality (Uber, Lyft, Airbnb) — others prove equally unprepared to leverage the positive economic benefits of the emergent idea had they embraced it earlier. Active scenario planning helps both the disrupted and those who may find new competitive advantage in anticipating the impact of change.

And in India, the uncertainty may be more about how disruptive the Gig Economy will be, and what it will mean within a regulatory and employment environment that is fundamentally different than the one found in America. Globally, the disruption of regulatory frameworks may lead to the very idea of employee and employment emerging as uncertain.

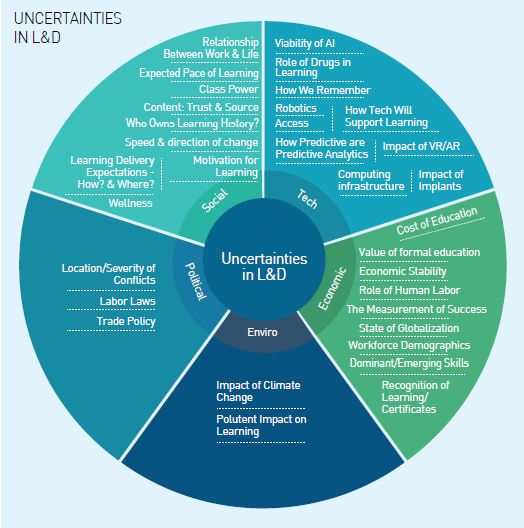

The next scenario planning phase involves documenting and sharing uncertainties. A common practice results in extremes for each uncertainty. In the example above, labor regulation might be documented with Supporting Traditional Employment on one side, and Empowering Emergent Work Relationship Models on the other. The L&D Uncertainty Illustration provides a sample of several areas that cause consternation to those thinking about the future of their organizations.

Diverse teams then vote on their perception of the factors based on which both are uncertain AND which are critically important to the question of HR’s role in 2030.

The highest vote getters become the critical uncertainties that form the matrix for the scenario plans. Usually more than two uncertainties rise to the top. This results in multiple matrices that must be evaluated. Scenario practitioners help teams hone down the assortment to a matrix that offers meaningful divergence and a rich story canvas in each quadrant. The next effort involves writing deep stories about the future—creating alternative answers for the focal question. At the end of the process, four very different futures emerge.

Uncertainties gain value that act internally consistent with each story, but may differ wildly from story to story.

Traditional employment has its story, as does the Gig Economy. Through the process, additional ideas emerge, that suggest other, mixed or extreme models of employment — each one offering an alternative context designed to answer the focal question.

Scenario Planning and HR

Creating stories is just the first major milestone in the process, and the least integrated with day-to-day work. At the end of the workshops, consultants lead teams through implications exercises that explore the impact of these alternative futures on roles, plans, processes, relationships and structures.

Scenarios eventually lead to deeper HR-implications like: Learning must be delivered in a fundamentally new way by 2030? We must be prepared to integrate the diverse employment models in a way that skills and performance meet our needs. We must plan for transitions as more-and-more robotics displace workers. Every scenario ends up with its own set of implications that suggest what needs to be done.

The real work comes while revisiting existing plans to make them more flexible and adaptive in light of the implications — and of change in general, now that the organization recognizes, perhaps even questions, the assumptions underlying them.

Some organizations create contingency plans, others create early warning systems that monitor the uncertainties so they can better anticipate change. As disruption evidence mounts, organizations should modify their plans to better navigate the emergent reality.

Even in organizations that don’t apply scenario planning strategically, the discipline can still pay dividends to the HR function.

Many organizations create ideal futures and work towards them. Believing that these visions can be achieved dismisses uncertainty. Single-mindedly working towards a particular future causes organizations to lose peripheral vision. When this happens, they become more vulnerable to unrelated events because they simply aren’t paying attention.

Scenario planning reminds HR leaders that there is more going on in the world than their daily experience permits them to see.

Putting a list of uncertainties on an office door, or cubicle wall, acts as a reminder that even today’s work may shift in importance because of factors outside of our personal, organizational or even governmental control.

Onward to the Future

HR faces many challenges as globalization, economic distribution and access to talent evolves. There is no right answer, and no trend watcher who will provide the answers. Each organization must understand the factors that influence its industry, and create scenarios that help it anticipate change, challenge assumptions and avoid surprises.

The most important function of scenarios comes from their ability to help people practice the future. Without a framework, imagining the future proves hard, and the results, inconsistent. People usually collapse their speculations and mix them with their hopes and dreams to weave a plausible story that doesn’t reflect robust analysis through challenging assumptions, or the existence of equally compelling alternative narratives. Scenario planning enforces both, while offering up a robust set of futures that help organizations confront the future, and themselves.

Three Steps Forward

Readers who want to embrace scenario thinking today should consider the following three activities to get started:

- For every item you “control”, write down at least one external factor that will influence, positively or negatively, the thing you think you control. (For example, hiring policy — hiring policy is influenced by local and national regulation; regulations are influenced by elected and appointed government officials and legislative bodies).

- Create a list of influences and forces shaping HR for which you are uncertain as to their ultimate role, or if they will even be an influence in the future — and keep it where it can be easily reviewed.

- As a leadership team, have each member write down five “facts” about HR you believed ten years ago that are no longer true, and five “facts” about HR today that you don’t think will be true in ten years. Are your plans flexible enough to manage through the next ten years of disruption?

If these exercises lead you to the conclusion that your plans, and your organization, are not as agile as they should be, a deep look at scenario planning may be required.